The YASEP does not use a Load-Store architecture, where memory is accessed through specific instructions. Unlike the huge majority of existing processors, it accesses memory through registers, somewhat like the CDC6600 CPU (except that the YASEP's registers are not dedicated for reads or writes). This saves a bunch of opcodes, increases memory bandwidth per instruction and keeps the instructions orthogonal.

The YASEP is architected around 16 registers. Each of these registers can be of one of 4 types. Here is the list in physical order:

It's more complex than a traditional RISC architecture but this reduces the number of needed opcodes because each opcode can perform several different actions.

Only two status registers (Carry and Equal) are available, they are accessed only through the conditional instructions. The method to save and restore them (should an exception occur) is not yet defined.

R1, R2, R3, R4 and R5 are normal registers, just like in other RISC architectures. One can write and read from them, without any implicit side effect.

; Example 1 MOV 1234h R2 ; Set register R2 with the value 1234h ; Example 2 ADD 4 R1 ; R1 <- R1 + 4 ; Example 3 ADD 42 R1 R3 ; R3 <- R1 + 42

These register typically hold temporary results of computations, loop counters, function call parameters... The extended instruction form can also post-increment or post-decrement them.

This register is less usual : PC is the pointer to the currently executing instruction. It is automatically incremented (by 2 or 4, depending on the instruction length) after each new instruction, and can be read and written by a program.

; Example : ADD 1234h PC A1 ; load the address PC+1234h into A1

; Example 1 MOV 1234h PC ; Jump to address 1234h ; Example 2 ADD 6 PC ; Jump to PC+6 ; Example 3 ADD 32 R1 PC ; Jump to R1+32

The YASEP's instructions are encoded on 2 or 4 bytes but all addresses have a byte granularity and the instructions are always aligned on even addresses, so the LSB of the address is always implicitly equal to 0.

However do not rely on this: writing an odd address to the PC could result in a CPU freeze/hang, to a software trap or even reboot. The LSB is a reserved bit, "nothing" may happen but always keep it clear!

A1, A2, A3, A4 and A5 are the "address registers". They contain the address where data will be read or written in memory. The extended instruction form can also post-increment or post-decrement them.

D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5 are the "Data registers" and they are closely related to the Address registers : A1 is bound to D1, A2 to D2 etc.

Each data register contains the value of the memory pointed by the associated Address register, the property Dx=memory[Ax] is preserved by the CPU for each pair (unless pointers are aliased).

Note that if a data register is read and written in the same cycle, as both a source and destination, the instruction effectively updates the memory location. This allows "RMW" ("read-modify-write") operations with a clean RISC core.

; Example 1

MOV 1234h A1 ; Point A1 to the address 1234h ==> D1 contains the value at this address

ADD D1 R3 ; Load the contents of [1234] and add it to register R3.

; Example 2

ADD 1234h R1 A4 ; point A4 to the address R1+1234h ==> D4 contains the value at this address

ADD R2 D4 ; load the contents of memory[R1+1234h],

; add it to R2 and put the result back at the same address

When used with post-decrement or post-increment features, these register can implement stacks. By convention, A5 is the stack pointer and D5 is the stack top. However, nothing keeps one from creating 2 or 3 stacks, or even moving the standard stack to other registers.

When two (or more) Address registers point to the same location (or memory word), consistency of the values of the Data registers should not be expected after writes. For example, if A1=A2 then writing to D1 will likely not update D2 with the new value.

In the early implementations, it is not feasible to simultaneously write up to 5 Data registers and compare 5 Addresses registers. The pipeline length and the gate count would increase too much. In the simplest cases, the Data registers act like small buffers, which are preserved in the register set through context switches.

However, it is possible that more sophisticated implementations solve this problem, using very different internal structures. Whole register banks might have to be saved through context witches.

In any case, race conditions are likely to occur. When aliasing is expected or possible, use critical sections (see the CRIT opcode) and use a single Address/Data pair to access these words. As illustrated by the last code example, read-modify-writes are best done (and shortest) when using just one register pair.

The YASEP is a Little-Endian computer architecture : the least significant byte is stored at the first/lowest address. You may use BSWAP to change the byte order in a register.

A Big-Endian version might be possible, code-named PESAY, though it's probably just a box to check in the configurator, that would define the order of the bytes on the the data memory bus.

The YASEP architecture is a byte-oriented architecture : any pointer can address a byte. But all the memory accesses are aligned on a natural word boundary.

Unaligned accesses do not trigger an error or raise an exception. The Data registers will always contain aligned data from the memory, as seen on the data bus, without shift or adjustment.

Or you could see it this way :

The "lost bits" address one of the bytes in the memory (half-)word.

; Example 1 (memory read) MOV 1231h A5 ; point A5 to the address 1231h (aligned on a byte boundary) MOV D5 R2 ; copy the word located at address 1230 into R2. ; Example 1 bis (YASEP32 only) MOV 1232h A1 ; point A1 to the address 1232h (aligned on a halfword boundary) MOV D1 R1 ; copy the word located at address 1230 into R1. ; Example 2 (write to memory) MOV 1231h A2 ; point A2 to the address 1231h (aligned on a byte boundary) MOV R2 D2 ; write the contents of R2 to memory location 1230 ; Example 2 bis (YASEP32 only) MOV 1232h A3 ; point A3 to the address 1232h (aligned on a halfword boundary) MOV R4 D3 ; write the contents of R4 to memory location 1230

If bytes or half-words are treated individually, certain instructions perform the adjustments :

; Example 3 MOV 1231h A5 ; point A5 to the address 1231h (aligned on a byte boundary) ESB D5 R2 ; align and sign-extend the byte at [1231], write the result to R2. ; Example 3 bis (YASEP32 only) MOV 1232h A1 ; point A1 to the address 1232h (aligned on a halfword boundary) ESH D1 R1 ; align and sign-extend the halfword at [1232], write the result to R1. ; Example 4 MOV 1231h A2 ; point A2 to the address 1231h (aligned on a byte boundary) IB R2 D2 ; take the lower byte of R2, align and insert the result into D2. ; Example 4 bis (YASEP32 only) MOV 1232h A3 ; point A3 to the address 1232h (aligned on a halfword boundary) IH R4 D3 ; take the lower half-word of R4, align and insert the result into D3

Like most computers, the YASEP works best when data are naturally aligned in memory. When in doubt, the user must explicitly check the alignment of suspicious pointers.

Unaligned words or half-words that may be stored over two consecutive words must be reconstructed with suitable instruction sequences.

Both YASEP16 and YASEP32 perform byte accesses with ESB, EZB and IB, as seen above. Bytes may only be stored in one memory word so they don't need more specific treatment.

YASEP16 only has ESB, EZB and IB. Consecutive bytes are combined with the SHLOopcode.

YASEP32 has ESH, EZH and IH for this purpose. They set the CARRY flag when the address register points to the last byte of a word, making handling code easier to write.

When the half-word is known to be at an even address (LSB0 condition) then the YASEP16 can directly use the pointer and YASEP32 can use the Insert/Extract instructions alone. Otherwise, both cores must use several instructions to fetch or store the individual bytes.

; unaligned half-word write of R1 to A1/D1 ; R1 is modified IB A1 R1 D1+ ; write the LSByte ROR 8 R1 IB A1 R1 D1- ROL 8 R1 ; eventually, if R1 is to be reused ; unaligned unsigned read of one half-word at A1 into R1 ; R2 is a temporary register EZB A1 D1+ R1 ; fetch the LSByte EZB A1 D1- R2 ; fetch the MSByte SHLO 8 R2 R1 ; Combine MSByte into LSByte ; unaligned signed read of one half-word ; R2 is a temporary register EZB A1 D1+ R1 ; fetch the LSByte ESB A1 D1- R2 ; fetch and sign-extend the MSByte SHLO 8 R2 R1 ; Combine MSByte into LSByte

Totally unaligned words on YASEP32 fall in two cases : whether the address is odd or even. In the first (most probable) case, it's simpler to combine bytes, while even addresses are faster to process with half-word instructions.

; Read an unaligned word on YASEP32 ; R2 is a temporary register EZB A1 D1+ R1 ; fetch the LSByte EZB A1 D1+ R2 ; SHLO 8 R2 R1 ; Combine into LSByte EZB A1 D1+ R2 ; SHLO 16 R2 R1 ; EZB A1 D1+ R2 ; fetch the MSByte SHLO 24 R2 R1 ; ADD -3 A1 ; optional ; evenly-aligned word read on YASEP32 ; R2 is a temporary register EZH A1 D1+ R1 ; fetch the LSHW EZH A1 D1- R2 ; fetch the MSHW SHLO 16 R2 R1 ; Combine MSHW into LSHW

(added to the blog on Tuesday 8 November 2011, 16:29)

(updated 2013-08-09 : added to YASim and simplified)

As the YASEP architecture specifies, there are 5 normal registers (R1-R5) and 5 pairs of data/address registers (A1/D1, A2/D2...) and it's quite difficult to find the right balance between both : each application and approach requires a different optimal number of registers.

When more normal registers are needed (suppose you need R6 or R7) then you could assign them to D1 and D2 for example. However you have to set A1 and A2 to a safe location otherwise chaos could propagate in the software (that would write D1 and D2 to random places).

Another unwanted situation appears if we use the Ax registers as normal registers : each write will trigger a memory read. And in paged/protected memory systems, this would kill the TLB by flushing it all the time and triggering an avalanche of page fault (and protection) exceptions...

A rather radical approach would use "status bits" (one per A/D pair) to disable the memory operations of the registers. The advantage is that two registers can be parked at once (using only 5 bits) but it gets harder to use with a compiler or from user software (you can play with pointers in C or Pascal easily, though you won't be able to define which pair is used). On top of that, adding status/control bits is usually a nightmare, since 5 more bits have to be saved/restored...

The YASEP uses a less optimal but more practical and less costly approach: the special value -1 in any A register disables the memory access for its D peer. This is called "register parking" or simply "parking". This avoids complex instructions and keeps the architecture user- and compiler-friendly. For example, the register pair is immediately available for memory access simply by writing a new valid address in the A register.

A register pair is "parked" when the A register has all its bits set, this is a byte address that shouldn't occur normally. The D register keeps its last value and can be written again without triggering memory write cycles.

The "parking address" is located at the "top" of the memory space, which is normally not used, or used for special purposes, such as "fast constants" addressed by the short immediate values (-8 to +7) :

MOV 6, A3 ; mem[6] contains a constant or a scratch value,

MOV D3,... ; whose address fits in 4 bits

Be careful because this "parking" system is not supported by all the YASEP implementations.

The following profiles support it : (not initialised)

And these profiles don't : (not initialised)

Anyway, parking is very easy to use:

; Park all the registers

MOV -1 A1

MOV -1 A2

MOV -1 A3 ; you better remember a fixed address

MOV -1 A4 ; so you can restore the stack later...

MOV -1 A5

Note that you can still access the word in memory, by using the evenly aligned address -2 for YASEP16 or -4 for YASEP32, since all the memory accesses ignore the Least Significant Bit of the address.

This means that in an implementation that does not support parking, (and assuming that the RAM is accessible there) at most one register pair may be parked without risks of corruption by other parked registers. One can always implement "software parking" by allocating other fixed locations to each pair, at the cost of more memory writes.

Architecturally, this parking mechanism is very light. The Data registers are usually "cached" by the register set. What the hardware parking system adds is just an inhibition of the "data write" signal that would occur normally each time the core writes to a D register.

Concerning the thread's backup and restoration, there are two cases to consider.

* When parking is not supported, you only need to save the address registers

because the data registers will be read again from memory

during restoration (only 11 registers to save assuming there is no alias!)

* If parking is supported, the D registers should be saved and restored

if the corresponding A registers equal -1.

In the end, register parking is not very complex (not as much as it seems). The hardware price is a few logic gates that detect the parking addresses to inhibit memory writes. For the software writer, it just means more registers on demand and it can be emulated if the YASEP has no parking hardware. You CAN have R6, R7 or R8 but then you'll have to restrict data access and give up A1/D1, A2/D2 and A3/D3. You make the choice !

The carry flag is a 1-bit register that stores the carry or borrow bit of the last executed ADD or SUB instruction. The carry flag is set when an addition overflows :

.profile YASEP16 MOV 5678h R1 ADD CDEFh R1 R2 ; R2 <- 5678h + CDEFh = 12467h > FFFFh so the carry is set. ADD 1234h R1 R2 ; R2 <- 5678h + 1234h = 68ACh <= FFFFh so the carry is cleared.

This bit can then be tested by a conditional instruction :

ADD 1234h R1 ; R1 <- R1 + 1234h (change the carry bit) ADD 1 R2 CARRY ; IF the carry bit is 1, then add 1 to R2

The SUB opcode is based on the addition so the borrow condition is the same bit as the carry bit of ADD. However, with SUB, the value is negated so the carry bit is set when the subtraction did not overflow :

MOV 4 R1 SUB 3 R1 R2 ; R2 = 3 - 4 = -1 ==> carry=0 SUB 4 R1 R2 ; R2 = 4 - 4 = 0 ==> carry=1 SUB 5 R1 R2 ; R2 = 5 - 4 = 1 ==> carry=1

Only the instructions that are flagged as "CHANGE_CARRY" can change the carry bit. Other instructions are CMPU and CMPS: they are similar to SUB but the destination is not written (write is inhibited).

The 32-bits adjustment instructions ESH EZH and IH also set or reset this flag to signal an out-of-word access (see above for examples). All the other operations will preserve this bit.

The carry bit can be tested many cycles after the above instructions are executed, even after function calls or returns. The best way to clear or set the carry flag is to cleverly use the CMPU/CMPS instructions with operands that will affect the carry flag in a deterministic way :

; clear the carry flag : CMPU R1, R1 ; R1 equals R1 so the carry can't be set. ; set the flag : CMPU 0, PC ; PC is (almost) always >0 so the carry is set.

Similar to the precedent carry flag, this second 1-bit register is updated by a couple of opcodes flagged with CHANGE_EQUAL.

It is complementary with the "register zero" condition that can test any register for having all the bits cleared. However, there are very few registers and barely enough room for temporary space so some instructions don't write their results back: CMPU/CMPS.

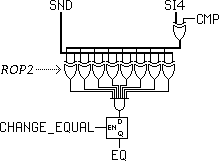

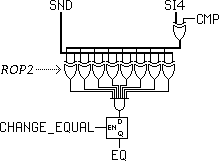

This flag reuses the ROP2 logic gates to compare both operands bit per bit, then the differences are AND-reduced to create the flag. The flag is set (1) when the operands are identical. This value is ony available through the EQ et NEQ conditions.